What is Shakuhachi?

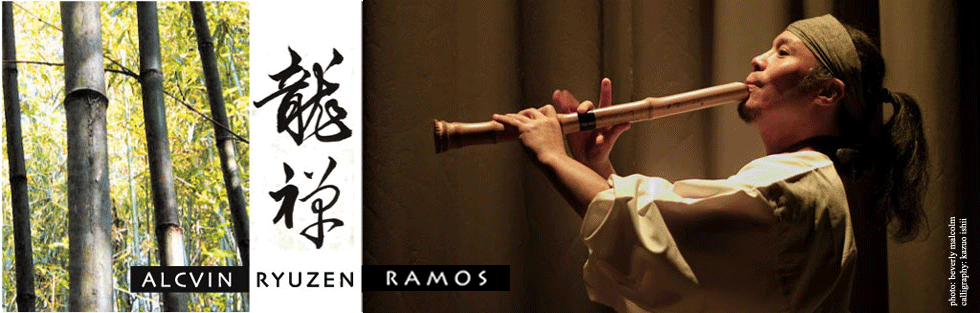

The Shakuhachi (kanji: 尺八); also referred to as take (kanji: 竹) is a Japanese end-blown flute which is held vertically like a recorder instead of being held transversely like the familiar Western transverse flute. A recorder player blows into a duct, also called a “fipple” and thus has limited pitch control. The shakuhachi player blows as one would blow across the top of an empty bottle, but the opposite edge of the shakuhachi has a sharp edge, allowing the player substantial pitch control. The five finger holes are tuned to a basic pentatonic scale with no half tones, but the player can bend each pitch as much as a whole tone or more. Shakuhachi are made from the root end of a bamboo stalk and is an extremely versatile instrument. Holes can be covered partially (1/4 covered, 1/2, 2/3, etc.) and pitch varied subtly or substantially by changing the blowing angle through dexterous control of one’s embouchure. Professional players can produce virtually any note they wish from the instrument, and play a wide repertoire of original Zen music (honkyoku), ensemble music with koto and shamisen (sankyoku), folk music (minyou), jazz, and modern music.

The name shakuhachi is derived from its size: 1.8. It is a simple compound of two Japanese words: The word “shaku” 尺 which means “foot” (as in English, both anatomical and as an archaic measure of length), which was roughly equal to 30.3 centimeters (ca. 0.994 of the English foot) and subdivided in ten (not twelve). The word “hachi” 八, in Japanese means the number 8, but here means eight tenth of the foot. Thus, shakuhachi literally means “one foot eight inches”; (almost 55 centimeters) which is merely the standard length of a shakuhachi. Other shakuhachi vary in length from about 1.3 shaku up to 3.8 shaku. The longer the shakuhachi, the lower its basic pitch with all holes closed. Although the sizes differ, they are all still referred to generically as shakuhachi. The bamboo flute first came to Japan from China and Korea and was first used in the gagaku (imperial court orchestra). The shakuhachi proper, however, is quite distinct from its continental ancestors, the result of centuries of isolated evolution in Japan.

Shakuhachi in the Medieval Period

During the medieval period, shakuhachi were most notable for their role in the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhist monks, known as komuso, who used the shakuhachi as a spiritual tool. Their sonic meditations (hon-kyoku) were paced according to the players’ breathing and were considered as something other than secular music. Travel around Japan was restricted by the shogunate at this time, but the Fuke sect managed to wrangle an exemption from the Shogun, since their spiritual practice required them to move from place to place playing the shakuhachi and begging for alms. They persuaded the Shogun to give them exclusive right to play the instrument. In return, some were required to spy for the shogunate, and the Shogun sent several of his own spies out in the guise of Fuke monks as well. (This was made easier by the baskets that the Fuke wore over their heads, a symbol of their detachment from the world.)

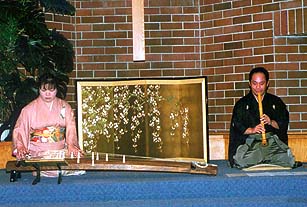

In response to these developments, several particularly difficult honkyoku pieces became well known; if you could play them, you were a real Komuso. If you couldn’t, you were probably a spy and might very well be killed if you were in unfriendly territory. This no doubt helped drive the Fuke sect to the technical excellence they were renowned for. In any case, when the Meiji Restoration occurred in 1868, the shogunate was abolished and so was the Fuke sect, in order to help identify and eliminate the shogun’s holdouts. The very playing of the shakuhachi was officially forbidden for a few years. Non-Fuke folk traditions did not suffer greatly from this, since the tunes could be played just as easily on another pentatonic instrument. However, the honkyoku repertoire was known exclusively to the Fuke sect and transmitted by repetition and practice, and much of it was lost, along with many important documents. When the Meiji government did permit the playing of shakuhachi again, it was only as an accompanying instrument to the koto, shamisen, etc. It was not until later that honkyoku were allowed to be played publicly again as solo pieces.

The Shakuhachi Today

New recordings of shakuhachi music are relatively plentiful, especially on Japanese labels and increasingly so in North America and Europe. The primary genres of shakuhachi music are: honkyoku (traditional, solo), sankyoku (ensemble, with koto and shamisen), shinkyoku (new ensemble pieces, composed after the Meiji period), gaikyoku (encompases sankyoku and other non-honkyoku traditional music), minyou (folk music), gendai kyoku (modern music; all non-classical pieces). The shakuhachi is also featured in western genres of music, including new age, smooth jazz, rock music, ambient, and avant garde, especially after being commonly shipped as a an instrument on various synthesizers and keyboards beginning in the 1980s. The shakuhachi can also be heard in a multitude of film and TV soundtracks and some contemporary world music.