“When Mahatma Gandhi first heard the sound of the shakuhachi, he supposedly wept and said he had finally heard the voice of the dead.”

–from Preston Houser’s article, Shakuhachi: Music of Myth and Memory, in Kansai Time Out #251, January, 1998.

The Meaninglessness of Zen in Shakuhachi: Suizen and Hon-kyoku

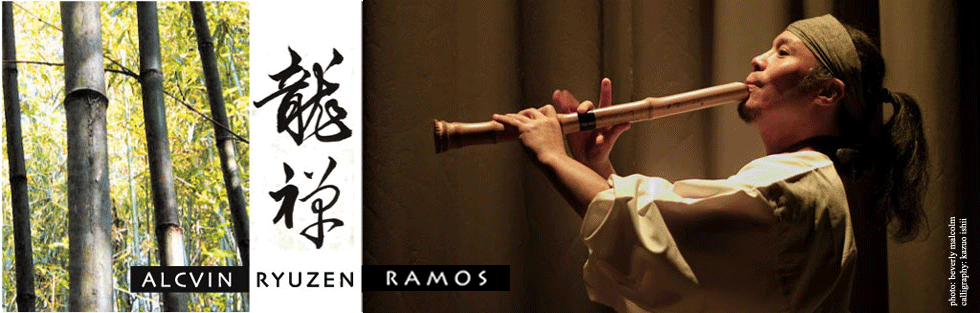

by Alcvin Ryūzen Ramos

According to the fundamental experience of Zen the aspect of shakuhachi (Japanese vertical 5-holed bamboo flute) in relation to Zen is meaningless, but the playing of its traditional pieces occupies a unique position in religious world music. It is the only true form of solo music in Japan. Suizen (kanji: 吹禅; blowing zen, or blowing meditation) is the practice of playing the shakuhachi bamboo flute as a means of attaining self-realization. The monks of old Japan who practiced suizen were called Komuso, or Monks of Nothingness and Emptiness (Ko: kanji: 虚 emptiness, mu: kanji: 無 nothingness, so: kanji: 僧 monk or priest). These monks belonged to a Rinzai Zen Buddhist sect called Fuke-shu, named after the legendary Tang Dynasty Chinese monk (Ch. P’u Hua) who first inspired the use of a bamboo flute as a meditation tool. These solo pieces on which suizen are based are called hon-kyoku kanji: 本曲, or original pieces. In the beginning, this term was not used. Around the 1870s shakuhachi players started to play in ensembles with koto and/or shamisen. To distinguish the solo zen pieces from these new pieces, they called these pieces, hon-kyoku and the new ensemble music, gai-kyoku kanji: 外曲 (outside/other pieces). These terms were used only within the shakuhachi world.

Prior to 1870 there were about 150 hon-kyoku. These are considered “koten” or “classical”, referring to the general body of the traditional pieces. These are distinguished from the “koden” hon-kyoku which refer to the three oldest pieces, Kyorei, Kokū, and Mukaiji.

In the late 19th century, Nakao Tozan formed the Tozan School of shakuhachi and composed his own hon-kyoku as did Hodo Ueda who formed the Ueda School of shakuhachi. Watazumi-doso of the 20th century rearranged old hon-kyoku as well as composed new ones and called his pieces, “Dō-kyoku” and never used the term hon-kyoku, insisting that playing them only on jinashi flutes (which he called “hocchiku”) was the only way to play his pieces. Today, many people are composing hon-kyoku-inspired pieces, which are sometimes called “neo-hon-kyoku”.

In the past, when playing hon-kyoku the state of mind was the most essential element, rather than musical enjoyment, therefore it wasn’t music per se. Indeed, it was prohibited for Komuso to play with koto (horizontal harp) and shamisen (three-stringed banjo-like instrument). The monks blew shakuhachi for their own enlightenment not for entertainment. However, since Zen Buddhism doesn’t emphasize deity worship, their music contains no sense of praise of faith. This is what is so unique about the practice of suizen as opposed to other religious musics. Today, hon-kyoku has evolved (some say devolved) into music, which is both profound and beautiful in its expression.

Very few people today actually understand or practice suizen in its original form. But hon-kyoku has turned out to be one of the most popular forms of music in the contemporary music scene today (in and out of Japan). There are various reasons for this. Many who have passed down the traditional hon-kyoku in modern times were not professional shakuhachi players insisting on keeping the practice of suizen by playing only hon-kyoku. Since these were mostly intellectuals isolated from the central musical scene in modern Japan where radical westernization took place, they concentrated on nurturing the spiritual side of hon-kyoku. But it was only a matter of time until western musical ideas affected hon-kyoku as well, which ironically was important to its survival. New forms of hon-kyoku began to appear which were much more dynamic and lively but still based on the original ideal of suizen. Hideo Sekino stated, “When we conceive The Art as the underlying spiritual representation of the ancient legend of the Komuso, the modern creation of hon-kyoku might have been the very effort to revive the dying legend from the overwhelming westernization in modern Japan.”

The past, present, and future are coloured with perceptions, fantasies, illusions from society’s conditioning and one’s personal experience. Once one realizes the fundamental meaninglessness and emptiness of Zen and shakuhachi, you are free to create your own world of deep, significant meaning for your shakuhachi life.

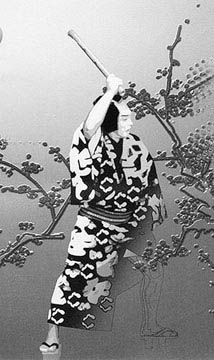

Shakuhachi and Bushido

After the death of Hideyori Toyotomi ca.1610 the Tokugawa family came under control ushering Japan into the Edo period, an unprecedented stretch of peace, which lasted 250 years. This was the golden age of the shakuhachi and other Japanese arts, which enjoyed support from the government, forming the base of today’s “traditional Japan”. During this time, the shakuhachi underwent a transformation from a 6-holed, thin piece of bamboo, to the 5-holed, root-ended bamboo flute that is most common today. Many samurai at that time whose masters were defeated by the Tokugawa Shogun were forbidden to carry swords and were left homeless. These were the “ronin” (masterless samurai), many of whom joined the ranks of the Komuso monks for spiritual focus as well as a chance to carry a weapon again, namely, the club-like shakuhachi. Earlier, this sect of monks (formerly known as Komoso, straw mat monks) attracted various riff-raff and beggars; but since the establishment of the Fuke-shu with its strict code of discipline (and support from the Tokugawa government), membership became exclusive to only those with samurai ranking, and the use of Shakuhachi was limited to only the Komuso. They traveled from place to place on pilgrimages to the various Komuso temples throughout Japan, playing their Shakuhachi for alms and meditation, concealed from the outer world by a large basket-like hat (tengai) that completely covered their faces. They were given special passes by the government, which allowed them free access across any border in Japan and on boats across bodies of water. Consequently, the government used many Komuso as spies.

The influence of Zen on the spiritual and aesthetic landscape of Japan was profound. Zen which simply means “meditation” (from the Chinese ‘ch’an’ and Sanskrit ‘dhyana’) appealed to the intellectual, ruling class, therefore was supported and permeated just about every art form at the time. From Zen came the ideas of spiritual selflessness and concentration of the mind. In the Samurai tradition of Bushido (Warrior Way) one dedicated his entire life to the protection and well being of his master and was trained in such a way as to merge totally with one’s weapon (e.g. the sword) as well as the environment and the opponent so as to have victory over him. When the samurai warriors were forbidden to carry their swords by the Tokugawa Shogunate, the ronin found it very easy to fit into the Komuso way since the concentration needed to learn Shakuhachi was similar to their sword training, and, the shape of the Edo period Shakuhachi resembled a hand held weapon, and no doubt was used as one as well.

In the daily life of the Komuso monks, it included morning zazen (sitting zen), suizen, begging, and martial arts training. In the rural Aomori Prefecture, Hirosaki district of northern Tohoku, Japan, one of the most famous schools was the Kimpu Ryū (Nezasa-ha) which developed a unique technique of breathing called “komi-buki” or “concentrated” or “packed breath”, where an intentional steady, pulse-rhythm is created while blowing the Shakuhachi by contracting and relaxing the diaphragm. It is said that it came about when after the Komuso Monks finished a hard training in their martial arts, which included jiujutsu (grappling and submission fighting) and kenpo (sword play) they would play their shakuhachi immediately afterwards, and the pulsing sound would be from their shallow breath and fast beating hearts. A lesser-known fact was shakuhachi’s connection with the Shogun’s Ninja (surveillance/assassin) force, a subject that deserves more research. According to shakuhachi scholar, Takashi Tokuyama, one famous Ninja named Sugawara Yoshiteru who became a komuso first in Kyoto and then in Edo often dedicated his performances to the Tokugawa Daimyo. Due to his skills as a Ninja, Sugawara became something of a small daimyo himself. He was permitted to build his own temple in Niigata, which became Echigomeianji. He composed the piece Echigomeian-hachigaeshi.

During the Meiji Reformation, the Fuke-shu of Komuso was abolished and many secret characteristics of this group were lost. Because of this historical loss we’ll never know entirely the reality of the Komuso. However, their instrument, the Shakuhachi has survived the westernization policy of the Meiji government. It’s use as a religious instrument (hoki) is now a musical one (gakki) utilizing western musical scale as well as Japanese, and played in ensembles, a practice which was previously prohibited.

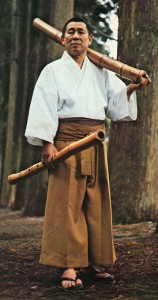

One of the most significant 20th century hon-kyoku players was Watazumi-do (Tanaka Masaru) (1910 – 1992). He combined a martial arts-like physical regimen complete with detailed breath exercises with Shakuhachi practice. His disciple, the late Yokoyama Katsuya (1934 – 2010) was also one of the most important professional shakuhachi players focusing on transmission of hon-kyoku in the late 20th Century and who’s influence continues to be felt today.

Today, in our post-modern age, shakuhachi music is appearing to those hemmed in by their material world. There is a renewed interest in a holistic approach to playing shakuhachi where mind, body, and spirit are developed along with musical ability. Many contemporary musicians are looking back at and discovering the beauty and enormous expression of traditional instruments, and the traditional style of playing shakuhachi. Shakuhachi music utilizes many sounds which do not fall within the standard western musical vocabulary. It makes active use of “non-musical” sounds or noise such as blowing, windy sounds, simulated animal sounds, as well as no sound, space, silence, which is a very important element in performance and symbolizes emptiness, selflessness, the basis of the life motto of the Komuso “Coming from nowhere, going to nowhere like the wind”. It also expresses that all things are sacred and related in this intricate web of change we call life.

The Main Schools of Classical Hon-kyoku in Japan

The following descriptions were compiled by email correspondences with hon-kyoku scholar, Takashi Tokuyama and are used with his permission. This is only a cursory look into the seven major schools of hon-kyoku in Japan. The lineages of these schools is extremely complex. So I will only touch on some basic information and a few key figures. For a more extensive and complete study, please refer to Adreas Gutzwiller’s dissertation on the Kinko Ryu, Christopher Yohmei Blasdel’s book, Shakuhachi: A Manual For Learning, and Riley Lee’s Phd. dissertation on transmission of hon-kyoku, and the Encyclopedia of Japanese Music (Japanese only).

About Myōan-ji

http://myouan-doushukai.org/

Myōan-ji temple in Kyoto was founded by Kyochiku Zenji (Kichiku), student of Hotto Kokushi, and was and is a prominent and influential center of Shakuhachi musicianship. The factors prompting Myōan-ji to concentrate on music (and by extension the Zen philosophy that might inform such an interest) were, in addition to the political importance of the temple, the high-culture tradition of Kyoto and the conservative perspective of Myōan-ji’s leaders vis-à-vis, art, religion and politics. Thus, in general, as Edo gradually became the center of a movement of popularized shakuhachi music, Myōan-ji continued to explore and refine a much more metaphysical Zen style. The stronger commitment to the musical tradition at Myōan-ji did not prevent the eventual inclusion of townsmen as ‘temporary’ Komuso or ‘musical helpers’, it is true, but it assured that the quality of the musicianship was first rate and that it followed fairly conventional lines. Several of the “abbots” of Myōan-ji were, infact, extremely accomplished musicians who gathered around them coteries of master players.

After some effort the present Myoan-ji temple was established in 1890. The new temple is considered the spiritual home of Shakuhachi playing today.

Kinko-Ryū

Kurosawa Kinko (1710-1771), founder of the Kinko style of shakuhachi, was a komuso monk born into a samurai family. He was responsible for taking the hon-kyoku of the past, which was concerned mainly with meditation, and adding a higher degree of musicality to it. He travelled all over Japan and collected 36 hon-kyoku pieces, which now make up the core of the Kinko style of shakuhachi. He also improved the instrument, perhaps improving the bore structure to access certain tones easier. It wasn’t until the second generation of the Kinko family that the delineation of a Kinko style was recognized since there were no styles of shakuhachi during his time.

How Kinko-ryū was established

It was well known that Kurosawa Kinko I was a brilliant player as was his student, Miyagi (Miyashi) Ikkan. But the son of Kinko I, Kinko II (Kurosawa Koemon) was not such a good player. Because of this, a conflict between Ikkan and the Kurosawa family developed. Ikkan felt that Kinko II was corrupting the style so he insisted the new style be called Ikkan-ryū. As a consequence, Kurosawa Kinko formally established the Kinko-ryū. From this point on Kinko-ryū started to be treated as different thing from the Koten Hon-kyoku.

So it would seem that what was called Kinko-ryū in the very beginning was just one sect of Koten Hon-kyoku. But since they treated themselves as a new and different entity from Koten, it became necessary for them to pursue their identity. During the time of Kurosawa Kinko III, the school gathered 36 hon-kyoku which were rearranged from older Koten pieces. In addition, the Kinko-ryū players developed new, more refined performance techniques; however most of their pieces sounded quite similar since only one person was doing all of the of musical arranging, most likely in short period of time. It is quite common that Kinko players couldn’t tell which pieces they were performing because they all sounded so similar. That being said, the Kinko-ryū do have a few brilliant stand-out pieces such as Shika no Tōne and Sōkaku-reibo. But many pieces like Hifumi and Hachigaeshi which contributed to the formation of Kyōto Meian-ha, sound quite similar to one another and which basically only utilize two melodic patterns.

During the Meiji restoration (1871) the sect of shakuhachi monks (Fuke-shu) was banned by the government. It’s use as a ritual tool was outlawed, but musically, it was enjoying great popularity among the secular classes, being used in ensemble with koto and shamisen (sankyoku). However, the shakuhachi was in serious threat of becoming obsolete, so the two men responsible for taking shakuhachi into the modern world were Yoshida Itcho and Araki Kodo, both of the Kinko style. They persuaded the government to let anyone play shakuhachi as a musical instrument, thus making it accessible to everyone. It was through their efforts that the musical popularity of the shakuhachi spread after it was outlawed as a religious tool. One of Araki Kodo’s most significant accomplishments was the development of a system of notation for the music of the shakuhachi utilizing the katagana script, which is read vertically (up to down, and right to left). Also, a system of dots and lines was created to indicate rhythm and tempo when gaikyoku (non-hon-kyoku pieces) were played. Three generations later, the disciple of Kodo II, Junsuke Kawase I (1870-1957) improved on the notation even more making it easier to read and more accessible to the public. He organized the Chikuyu Sha shakuhahchi organization, which became the largest organization within the Kinko style and has membership throughout the country and the world. His music has become the standard for all Kinko players.

The Oldest Honkyoku Styles

The oldest pieces are referred to as “Koten Hon-kyoku” (traditional zen music). But one must be careful as historic details are quite obfuscated to say the least. Apart from the oldest, most fundamental 11 pieces from Fudaiji Temple in Hamamatsu, there are also different styles of hon-kyoku from other parts of Japan such as Kyūshū and Tōhoku (Ōshū). In the beginning, there was only Koten (traditional) hon-kyoku which was synonymous with Kinko-ryū from the Kantō area. Furthermore, many shakuhachi people in Japan misunderstand that Koten Hon-kyoku is the same as Meian-ryū. It is more accurate to refer to Kyoto Myoan-ryū as Myoan-ha (ha means sect) which is technically a sect of the Koten Hon-kyoku, rather than the overall body of Koten Hon-kyoku itself.

Myōan-Shinpo Ryū

From http://www.komuso.com/schools/index.pl?school=39:

In Kyôto immediately after the dissolution of the Fuke sect, the Myôan Shinpô ryû (‘Myôan True Dharma Sect’) was important in continuing the hon-kyoku tradition after the Fuke sect era. Founded by Ozaki Shinryû (1820-1888), its leading proponent was one of Ozaki’s students, Katsuura Shôzan (1856-1942). Shôzan became the head of Myôan kyôkai in 1881, and was influential amongst a great number of honkyoku players. He left Myôan kyôkai soon after the arrival of Taizan. Outliving almost all of his contemporaries, Katsuura came to be known as the last of the komusô. Although there is no longer an organization called Myôan Shinpô ryû, much of Katsuura’s repertoire continues to be transmitted today both by individuals and as part of the repertoire of other organizations.

Shinpō-ryū included various musical elements from folk songs, popular songs of those days, music from horizontal flute (yokobue) which were forgotten when Higuchi Taizan started teaching the Fudaiji pieces.

Edited by Jeffrey Jones with permission from Dr Riley Lee’s PhD Thesis Yearning For The Bell; a study of transmossion in the honkyoku tradition. 1992 University Of Sydney

Kinpu Ryū (Nezasa-ha, Aomori)

Located in Hirosaki (Aomori prefecture), this school has very special ways of playing using a technique called “komi-buki” (packed) blowing, and “chigiri” (special chin movement technique). Many practitioners in the area were samurai and were asked to master Kendō swordsmanship and this style of Shakuhachi which was promoted by Lord Tsugaru in the Edo Period. Later, players who loved this music tried to imitate his this style, and perfected a simpler form of playing. A more detailed description of this school can be read here: http://www.kinpu-ryu.com/

Seien Ryū

One of the original schools of Koten hon-kyoku from Hamamatsu (Shizuoka Pref.). The original 11 hon-kyoku from Hamamatsu that were taken to Kyoto by Higuchi Taizan (formerly Suzuki Kōdō) have its origin in the Seien-ryū.

Myōan-Taizan Ha

The following information from: http://www.komuso.com/schools/index.pl?school=4:

One of the most prominent schools within the Myoan-Ha, is the Taizan-ryu. It was founded by Higuchi “Kodo” Taizan (1856-1914) who first was a student of the Seien style Shakuhachi and in 1890 went to Kyoto where he joined the Myoan Society becoming an instructor. He spent much of his time collecting and organizing pieces from the Myoan tradition as well as many others. His outstanding talents as a player and his work expanding the repertoire of the Myoan Society revitalized the Myoan tradition. He is called “the founder of the restoration of the Myoan-ha”. “Kodo” compiled the Hon-kyoku that is currently used in the Myoan-Ha today. He became the 35th Kanshu of the temple Myoanji.

Information compiled from email correspondence with Dr. Norman Stanfield and and Christopher Yohmei Blasdel’s “The Shakuhachi a manual for learning” and “ Shakuahachi Zen the Fukeshu and Komuso” by James Sanford. List of Kanshu of Myoan-ji Temple translated from a book by Tomimori Kyozan by Morimasa Horiuchi.

Kyūshū-kei

During the Meiji Restoration, the komuso temple in Hakata in Fukuoka named Icchō-ken, was left in ruins. In 1951, Iso Jōzan, a komuso priest and his wife, Ikkō Jōzan, who was also a fine player, saved the temple, relocating it to the Saiko-ji within the Shofuku-ji Rinzai Zen Temple complex, and revived the tradition of the Fuke Komuso shakuhachi religion. Their son, the present abbot of Icchō-ken, Iso (Akira) Genmyō is very active as a buddhist priest and shakuhachi teacher with many students from all over Japan and in Europe. He caries the line of Icchō-ken, Taizan-ha, Ōshū-kei, and Kimpu-ryū which he learned from his parents.

Throughout Kyūshū, the piece known as “Sashi” is most important, which spawned many variations which are completely different from the original Sashi. The famous piece “Ajikan” was originally called Sashi, from Icchō-ken.

More interesting information about Iccho-ken can be found here: http://myoanshakuhachi.blogspot.ca/.

Ōshū-kei

Coming soon…

Tozan-Ryū

Nakao Tozan (1876-1956), founder of the Tozan style of shakuhachi, was born in Osaka. He came from a musical family, his mother being a daughter of a famous shamisen master, Terauchi Daikengyo of Kyoto. He learned how to play shamisen as a child and learned how to play shakuhachi on his own. When he was in his late teens he joined the Myoan Society of shakuhachi monks and developed technique with them. In his early 20’s he opened up his first shakuhachi studio in Osaka. This was the beginning of the Tozan style. In 1904 he began composing pieces for the shakuhachi which later became the hon-kyoku of the Tozan style. He was very knowledgeable about western music, creating new performance and teaching methods, and revising the music for shakuhachi. Consequently, he was very successful at popularizing the shakuhachi, attracting a large following, especially among the youth of Kansai. He moved the Tokyo in 1922 and collaborated with the famous koto composer, Miyagi Michiyo; but Kansai still remains the center of the Tozan school.

Evolution of Hon-kyoku

Coming soon…

Ueda Ryu

Chikuho Ryu

Watazumi Do

Kenshukan

Zensabo

Comparison between Schools

Unlike the Tozan school, the Kinko and Myōan schools have no central organization (iemoto). This has allowed the Kinko and Myōan schools to enjoy more diversification and freedom of expression. To further define each particular school, they started inserting their uniquely shaped utaguchi into the shakuhachi mouthpiece. Kinko is angular; Tozan is crescent-shaped, and the Myōan is a blend of the two. (With the development of new fortifying materials (e.g. super glue) for shakuhachi making, some modern schools such as the Zensabo stopped using utaguchi inserts preferring to keep the plain bamboo utaguchi.)

Students of the Kinko school who were proficient enough usually broke off and formed their own sects and created their own gaikyoku and notation styles (but was usually based on the original script of Araki Kodo I).

The Kinko and Tozan schools however emphasize musicality and place high emphasis on gaikyoku training, especially playing with an ensemble of jiuta shamisen and Ikuta, Yamada, and Sawai styles of koto. Furthermore, both schools have always had a positive attitude towards new music and are active in the contemporary music scene. In Myōan emphasizes suizen (blowing meditation), as well as intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual development and enjoyment.